Because its products and services permeate our lives, Google has tremendous power. If the company cannot even pretend to care about its internal “Ethical AI” co-leader, how much do you think they care about the rest of us?

***

Dr. Timnit Gebru and I do not know each other. I have never met her and she probably is not even aware I exist. And yet, she is very important in my life. Not only in my life, but in your life, too. Indeed, I believe Dr. Gebru is extremely significant for everyone and I will explain why below.

Before that, let me recap briefly what happened last week that inspired me to write this, in case you have never heard of Dr. Gebru before. (It is very well possible that you have not — as I may not have if I weren’t researching the social aspects of algorithmic systems for a living.) However, you certainly know Dr. Gebru’s former employer: Google. You may even have heard of her area of work: at Google, Dr. Gebru used to be the co-lead of the Ethical AI team. And maybe, just maybe, you have even heard of her ground-breaking research (with Joy Buolamwini) demonstrating how face recognition algorithms are most accurate for faces that are male and caucasian and perform terribly for people of color, especially women. [Dr. Gebru’s record goes far beyond this one example I picked. Yet it is the one I have heard and seen mentioned most frequently as the go-to example in industry, policy and public discussions of “algorithms are not neutral”.]

On the morning of December 3, I checked my twitter feed and discovered Timnit Gebru’s tweet, published a few hours prior, announcing her discovery that Google had fired her. She wrote that her employment had been terminated immediately with reference to an email to an internal mailing list.

The news spread like a wild fire and, within hours, disputes over details and definitions broke out. What exactly did her email to the mailing list say? Was this the real reason she was fired by Google? Was she actually fired or did she resign? And even if she was fired: did she deserve to be fired? But here’s the thing: although some of the answers to these questions are informative (and even the questions themselves are very telling!), I will not discuss internal e-mails and information about individual people at Google here. For the point I am trying to make, none of them really matter.

***

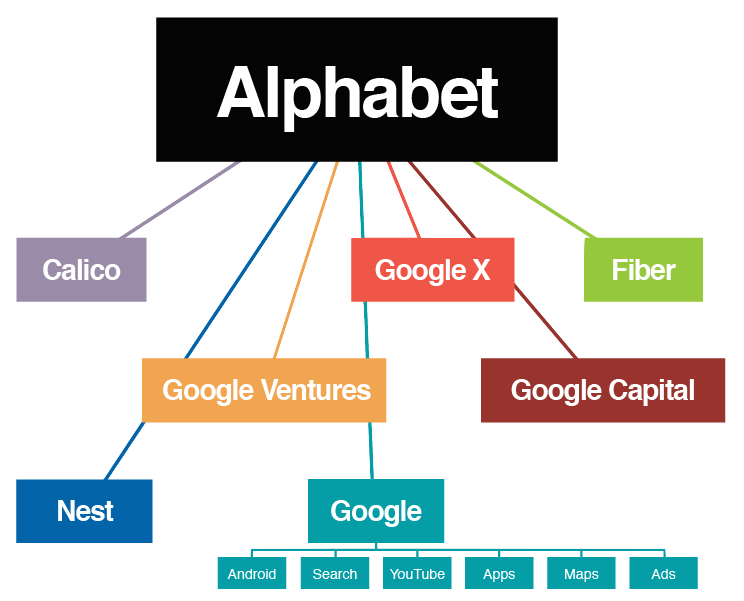

Google is still most well-known for the web search engine at the root of its success. But the company is much more than Google Search. Although there is a tendency to underestimate it, it is actually impossible to overstate the power Google/Alphabet has in Europe and North America (and beyond). Arguably, the company has more data on most individuals, industries and societies than any other corporation. Google shapes how people create, circulate, seek out, “consume” and treat information and it is able to identify when and how people sleep, eat, work, travel, socialize, learn, read and write. The company can leverage this knowledge in all domains of our lives for its profit and purposes. Because Google is much more than web search…

There are of course Google Drive, Google Maps, Google Earth, Gmail, G Suite and the other online services, including Google’s advertising infrastructure. But there is YouTube. And the web browser Chrome. And the most popular mobile operating system Android. And consumer electronics such as smartphones (Pixel), laptops (Chromebook) and smart assistants and devices (Google Home, Nest). And Google Pay. And the so-called “other bets.” They were split off as separate entities when, in 2015, Google became your regular international corporation by restructuring its corporate assets and founding Alphabet in the process. These other bets remain nonetheless relevant when talking about Google, notably the transportation venture Waymo, Calico (a biotech company focused on longevity), CapitalG and Google Ventures (private equity and venture capital funds), X Development (an R&D organization), Jigsaw (a technology incubator), Google Access&Energy, and the life science venture Verily, making big forays into the health sector.

Credits: Alvandria, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Add Google’s financial muscle to the mix — the company reported a 3rd quarter revenue record of 46.02 billion U.S. dollar in 2020 and has currently reached its all-time high of 1.23 trillion(!) U.S. dollar in market valuation — as well as a trove of lobbyists and policy-shapers close to governments and within consultancies, and you may start to realize why I wrote that Google’s power cannot be understated.

***

Artificial intelligence (AI) is central to many products and services of the contemporary information technology industry. When the company announced their AI principle on June 7, 2018, CEO Sundar Pichai wrote:

We recognize that such powerful technology raises equally powerful questions about its use. How AI is developed and used will have a significant impact on society for many years to come. As a leader in AI, we feel a deep responsibility to get this right. So today, we’re announcing seven principles to guide our work going forward. These are not theoretical concepts; they are concrete standards that will actively govern our research and product development and will impact our business decisions.

We acknowledge that this area is dynamic and evolving, and we will approach our work with humility, a commitment to internal and external engagement, and a willingness to adapt our approach as we learn over time.

(from https://blog.google/technology/ai/ai-principles/, emphases mine)

Google’s seven principles for AI were widely reported on by media outlets, although the company was neither the only organization to publish ethics principles for AI nor the first. [In fact, at the end of the decade there had been so many publications of AI ethics principles that it became hard to see the forest for the trees. Therefore, at my former workplace (the Health Ethics & Policy Lab at ETH Zurich), we decided to provide an overview and analysis of such publications.]

These ethical principles are not even Google’s only initiatives in the domained called “AI ethics”. Browsing around the company’s website you may stumble upon suggestions and documentation of “responsible AI practices“. You can find research papers, tools, datasets, links to initiatives aimed at fostering a diverse workforce, and even novel approaches such as model cards.

Most prominent was also Google’s creation of ATEAC: the Advanced Technology External Advisory Council. The ATEAC has colloquially been called Google’s “AI ethics council” and was announced in spring of 2019 with the stated aim of “consider[ing] some of Google’s most complex challenges that arise under our AI Principles, like facial recognition and fairness in machine learning, providing diverse perspectives to inform our work”.

The fact that Google has already had an internal “Ethical AI” team since 2017, founded by Meg Mitchell, is not widely known outside the industry. Until last week, Dr. Timnit Gebru was the technical co-lead of the Ethical AI team.

***

Ethical is not the same as legal: not everything that is legal is also ethical, and not everything that is illegal is also unethical. Legal is about what is and is not lawful. Ethics is about what should and should not be, from a moral standpoint. There are many overlaps and, ideally, laws are also ethical. But a discussion about what is ethical, or not, cannot be limited to what is legal or not.

***

Ethical AI is a widely discussed and disputed notion for several reasons. Untangling this would be a whole other article, but highlighting just two tensions will help illustrate the issue present: one is about the technological solutions to “achieve” ethical AI vs the processes that will enable the existence of “ethical AI”, and another one is about the question whether it is even possible for a corporation such as Google to be ethical. They are, of course, related.

I will not expand on the first tension here but refer to two important articles on the topic instead: this excellent Nature piece by Dr. Pratyusha Kalluri, and the award-winning article “Technology Can’t Fix Algorithmic Injustice“.

The second tension brings me back to a Friday night in May 2018. I had the priviledge to attend a panel discussion between Tarleton Gillespie, Ben Tarnoff and the Tressie McMillan Cottom. To be honest, I do not recall the exact quote nor the exact circumstances — a discussion about the power of big tech companies? about the lawmakers’ inaction? about the futility of consumer boycotts? probably all of them — but I vividly remember one particular affirmation Dr. McMillan Cottom made that night: workers are vectors of change.

At that time, I did not fully understand what she meant in the context of the panel (despite the fact that a few weeks earlier there’d been big internal protests at Google against the company’s involvement in “the business of war”, a.k.a project Maven). Then, three months later, in the beginning of August 2018, the public, including many people working at Google, learned about the existence of project Dragonfly, a web search engine for China that censors in compliance with the Chinese government. Google employees of the company got organized. And the implications of Dr. McMillan Cottom’s statement finally made sense to me.

Employees can be vectors of change. They can nudge, prod, force, inspire, encourage their company towards doing the right thing. Workers may wield some influence in economic settings where end-users have none.

The list of companies behaving unethically is long. When it comes to big tech and AI, it has even been suggested that “ethical AI” itself is an unethical farce, a corporate tactic aiming at avoiding regulation. Yet, if companies behave more ethically even if it is for the wrong reasons, are we not all better off anyway? Well, it depends on who the “we” is. If the premise is that a company actually behaves more ethically, this must include how the company works internally and it must comprise employees. Behaving ethically cannot be done with outwards facing principles and panels alone. It cannot be done with ethical entities alone. An ethical company also needs to be based on ethical processes, which make room for hard questions about what should be.

***

Companies benefits from the people it employs. Such benefit can take many forms, for example labor, expertise, connections, or reputation. By “company” I do not mean the people it is comprised of but the economic, structural entity in whose name people act.

Timnit Gebru holds a a PhD from the prestigious Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, where she studied computer vision under Fei-Fei Li. Prior, she had also worked at Apple, and after graduating she did a postdoc at Microsoft’s FATE (Fairness, Accountability, Transparency and Ethics in AI). Dr. Gebru also co-founded the Black in AI community (together with Rediet Abebe) and the FAccT Conference. Her research is both innovative and important, widely recognized and appreciated.

It is evident that Google could benefit immensly from employing someone with the expertise of Dr. Gebru. In addition, by hiring a leading AI researcher who happens to be a woman of color, the company takes a small step in correcting its abysimal diversity statistics (only close to one third of Google employees happen to be women, and in Google’s U.S. workforce, black women only make up 1.6%). [In Sillicon Valley, Google is unfortunately not an outlier in this regard.]

There is a third, more indirect benefit for Google, though it is mainly reputational. Dr. Gebru and her work aim at making this world a better place. If she agrees to work for Google, the company cannot be that bad, now can it. Indeed, a company that Dr. Gebru is willing to work for simply cannot be entirely unethical… it must at least be trying to do better, right?

The fact that Dr. Gebru is not part of Google anymore is a loss for the company because Google loses both expertise and reputation: it is hard to keep even an ounce of good faith in Google if the company is not willing to retain a brilliant black AI expert who is trying to make it more ethical.

But most of all, the fact that Dr. Gebru is not part of Google anymore is a a loss for all of us: because both Google and AI are powerful in today’s world, we are all worse off if Google so very clearly does not value what Dr. Gebru has to offer.

***

Disputes over what happened and who did when what exactly seem unproductive to me in this regard. Even if they were resolved, they do not change the outcome and, thus, the conclusion: Google very clearly does not value neither Dr. Gebru herself nor her expertise.

But I want to make explicit that I, of course, believe Dr. Gebru. I am horrified that she was effectively fired from one day to the next for doing her job, which is: asking hard questions about what should be, and pushing the company to do better and be more ethical. I have seen people point to Google’s supposed rationale for firing her, but these arguments are legalese sugarcoating of the fact that Google wanted to look like it was doing ethics without actually doing ethics.

Behaving more ethically requires more ethical processes. Well, Dr. Gebru spoke out against unethical practices and processes and demanded accountability; her recent research warns of severe risks of AI for people and the planet — I can hardly think of a better opportunity for an AI company to behave more ethically than to do listen to, learn from, and empower someone like Dr. Gebru.

Google, however, clearly has no interest in behaving more ethically, for whatever reason. Absent stringent regulation, only organized internal pushback at great personal cost seems to positively impact the company’s unethical policies. [You may want to keep in mind that Google is not necessarily doing worse than other technology company in this regard, on the contrary. Some of Google’s behaviours like its comparatively transparent research outputs may even make it fare better compared to other coporporations. But the the bar is low and Dr. Gebru has just been fired, so please excuse my specific focus here.]

Remember Google’s “AI Ethics council”? Its make-up, so blatantly motivated by politics, incited an internal protest petition and ATEAC ended up being disbanded a few days after it was announced. What should Google have done differently? The MIT Technology Review published several relevant recommendations, including mine (stop treating ethics like a PR game!), but it is Prof. Anna Lauren Hoffmann’s suggestion I want to highlight here: “Look inward and empower employees who stand in solidarity with vulnerable groups.”

Remember the Google walkouts of 2018, sparked by the $90 billion pay-out to a high-ranked employee accused of sexual assault? The organizers paid a great individual cost. What should Google have done differently? Probably everything, as the U.S. National Labor Relations Board found that the company illegally surveilled and fired employees for organizing. Ironically, these news broke the same day Dr. Timnit Gebru announced she had been fired…

***

Now what?

For a start, I have signed my very first online petition asking for accountability regarding Dr. Gebru’s termination (I even signed twice due to an e-mail error). Although I am not overly worried about where she will land, I am very sorry for what she has been experiencing.

This is of course about Dr. Gebru. Yet this is also about so much more. It is also about the power of corporations. It is also about underrepresented people in the workplace. And ultimately, it is about all of us. The way Google treated the person they hired to do ethics highlights the profoundly undemocratic and unjust configuration between people and corporations, which may behave in authoritarian ways without consequences. What happened illustrates the unilateral power of tech companies, which significantly shape our world and our lives without ever having to take into account the slightest amount of critique.

This is not how things should be.

This is not ethical.

Pingback: 11 links to dive into the ethics of artificial intelligence | Sociostrategy